Multithreading

Core Concepts

-

Cool Explanation of Process and Multithread .

-

Uses a bit of machine code to demonstrate common multithreading issues.

-

-

-

He presents everything very well. Great talk.

-

Assumes you already know what mutex, deadlocks, etc., are.

-

It's an intermediate talk, not beginner.

-

Pt2 is very technical for C++, basically explaining a library with techniques.

-

Maybe useful, but not relevant atm.

-

-

Process vs Threads

-

.

.

-

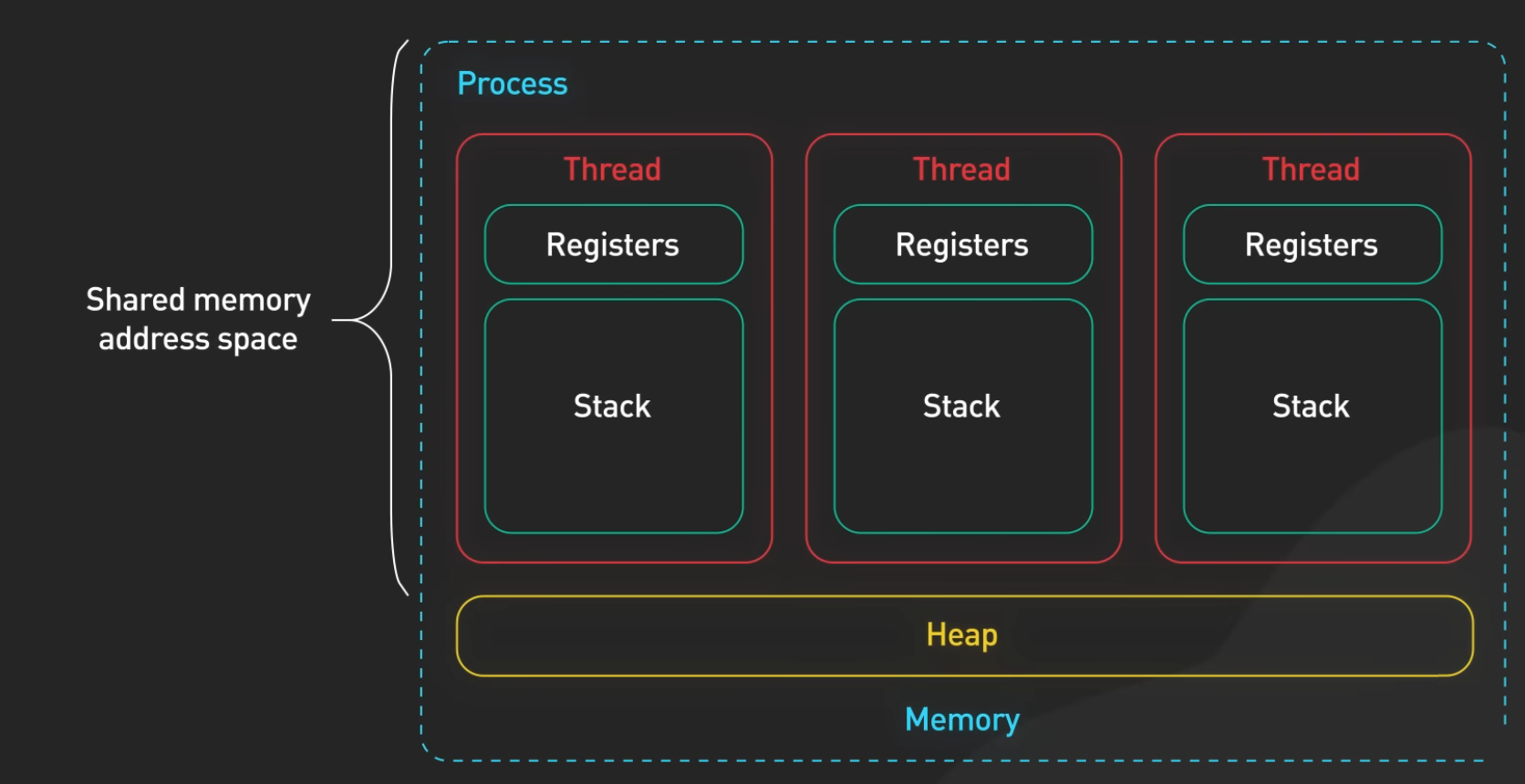

Threads are execution units within the same process.

-

A process can contain multiple threads, all sharing the same process memory space.

-

.

.

-

Memory :

-

All threads (including main) share the same heap, code, and global data, but have independent stacks.

-

Memory shared among all threads :

-

All heap-allocated memory.

-

All memory of global/static variables by the main thread.

-

Main thread stack.

-

Each thread has its own stack. However, pointers to main thread stack variables can be passed to other threads, risking out-of-scope use.

-

Passing a pointer to a local main thread variable to another thread is risky if main exits scope before the other thread finishes.

-

-

-

Multithreading

-

Technique that allows concurrent execution of two or more threads within a single process.

-

Threads can perform tasks independently while sharing process resources.

-

Multithreading is both:

-

A concept (the idea of using multiple threads).

-

A strategy if used directly (e.g., "We use raw threads for parallelism").

-

-

Models :

-

User-Level Threads :

-

Managed by the application, no kernel involvement.

-

-

Kernel-Level Threads :

-

Managed directly by the operating system.

-

-

Hybrid Model :

-

Combines user and kernel threads.

-

-

Main Thread

-

It's the first thread that starts executing when the process is launched.

-

Automatically created by the OS when starting the process.

Resource

-

Something you don't want 2 threads to access simultaneously.

-

Ex:

-

Memory location.

-

File handle.

-

Non-thread safe objects.

-

Starvation

-

~When a thread finishes work much faster than another and ends up doing nothing?

Race conditions

-

When a Resource is accessed by 2 or more threads simultaneously, and at least one of them is a write .

-

Causes Undefined Behavior ; it's critical to avoid this.

Read with concurrent Write

-

"If a thread is modifing a variable and I try only READING this variable on a different thread, what can I expect? I assumed that only 2 thing could happen: I either get the old value, or the new value"

-

More than just “old or new” can be observed in practice. Memory effects include seeing the old value, the new value, a torn (partially-updated) value, or behavior caused by compiler/CPU reordering (stale values, values observed in surprising orders). Which of those can occur depends on alignment/size, hardware cache-coherence, and the language memory model and compiler.

-

atomic single-word writes (aligned to machine word)

-

On most modern CPUs a naturally aligned write of a machine-word-sized integer is atomic at the hardware level — the hardware will not present a half-written word to another core. In that case the reader will typically see either the old value or the new value (once the write becomes visible).

-

Caveat: “typically” is not the same as “guaranteed by the language.” If your language/compiler does not declare the access atomic (e.g., plain

intin C/C++ pre-C11), the compiler may optimize assuming no concurrent writer, which can produce surprising behavior even if hardware atomicity holds. Use language atomics to get defined semantics.

-

-

multi-word values or misaligned accesses → tearing possible

-

If the write spans multiple machine words (for example writing a 64-bit value on a 32-bit CPU, or a struct covering multiple words) or is misaligned, hardware can perform the write as multiple smaller writes. A concurrent reader may see a value composed of some bytes from the old value and some bytes from the new value — a torn value (part old, part new). That is not just “old or new.”

-

Example: on a 32-bit CPU writing a 64-bit integer might execute as two 32-bit stores; another core can read between them.

-

-

caches, store buffers, and visibility delays

-

Writing a value usually goes into the CPU core’s store buffer first; the write becomes globally visible when it propagates to other cores’ caches (through the coherence protocol). During that window another core may not yet see the new value and will read the old one. So a reader can see the old value for some time even after the write completed on the writer core.

-

The cache-coherence protocol (MESI / variants) guarantees eventual coherence, but not instantaneous visibility without synchronization/fences. On most coherent systems, once the write is visible it will appear as a single update for naturally aligned single-word writes; for multi-word/misaligned it may be torn.

-

-

compiler and CPU reorderings (visibility and sequencing)

-

Compilers can cache a value in a register, reorder memory operations, or eliminate reads/writes if the code is not marked atomic/volatile as required by the language semantics. That means the value you read might be a stale register value or the read might be optimized away.

-

CPUs reorder loads and stores (the allowed reorderings depend on the architecture). Without proper memory-ordering primitives (fences/atomic memory orders), the observed order of multiple memory operations can differ across threads.

-

-

language-level oddities (Java “out-of-thin-air”, C/C++ undefined)

-

In Java, unsynchronized data races allow a wide set of behaviors — theoretically even values that seem “out of thin air” in some relaxed executions (practical occurrences are rare and subtle).

volatileorAtomic*enforces ordering/visibility. -

In C/C++ a plain non-atomic concurrent write+read is a data race → undefined behavior. That means anything can happen (including program crash, or surprising compiler-generated assumptions that make behavior impossible to reason about).

-

Deadlock

-

Occurs when two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting on each other’s resources.

Lock-Free

-

When using locks, sections of the code that access shared memory are guarded by locks, allowing limited access to threads and blocking the execution of other threads.

-

In lock-free programming, the data itself is organized such that threads don't intervene much.

-

It can be done via segmenting the data between threads, and/or by using atomic operations.

Context Switching

-

The CPU switches between threads to provide concurrency.

-

Involves saving and loading thread states.

-

Has performance cost due to saving/restoring CPU registers, etc.

Parallelism

-

Executing multiple tasks simultaneously, typically on multiple cores or processors.

-

Focuses on true simultaneous execution .

-

Requires multiple physical or logical processing units.

-

Common in CPU-bound workloads (e.g., simulations, rendering).

-

Ex :

-

Using 4 cores to calculate physics updates for 4 game entities at the same time.

-

"Multiple workers doing different tasks at the same time ."

-

Concurrency

-

Managing multiple tasks at the same time, but not necessarily executing them simultaneously.

-

Focuses on interleaving execution of tasks.

-

Can occur on a single core .

-

Requires context switching.

-

Involves task coordination, scheduling, and synchronization.

-

Exs :

-

"One worker juggling multiple tasks — rapidly switching between them."

-

Switching between user input handling and background loading in a game loop.

-

-

About Multiplexer :

-

A multiplexer is a building block, not a full concurrency strategy.

-

Enables event-driven concurrency on a single thread, often forming the basis of asynchronous runtimes.

-

Common in network servers, GUIs, and I/O frameworks.

-

Sleeping

-

"odd thing: while sleeping for 0.8 ms in my main loop I get 15% cpu usage, but if I sleep for 1ms then the cpu usage drops to 1%".

-

This behavior is actually expected and reveals insights about how modern OSes handle thread scheduling and sleep durations:

-

Windows (and most OSes) have a default scheduler tick interval (usually 15.6ms or 1ms depending on system)

-

Below ~1ms, sleeps are often implemented as busy-waits (explaining your 15% CPU at 0.8ms)

-

Above 1ms, the OS can properly suspend the thread (hence 1% at 1ms)

-

-

The 1% vs 15% difference represents your CPU entering deeper sleep states

-

Wow, crazy.

-

Thread

Thread

-

A thread is the smallest unit of execution within a process.

-

Multiple threads can exist within the same process and share the same memory space.

TID

-

Thread ID.

PID

-

Process ID.

How many threads can I have per core?

-

A thread is a unit of execution, a core is a physical CPU processing unit.

-

OS defines the relationship by scheduling threads on cores.

-

Creation Limit :

-

Number of threads you can spawn.

-

There is no fixed limit on how many threads you can create per core; you can spawn hundreds or thousands.

-

This can be hundreds to millions, but most will be idle or waiting.

-

Often limited by OS, memory, and thread stack size.

-

Linux:

-

Depends on

ulimit -u, memory, stack size (e.g., ~30K–100K).

-

-

Windows:

-

Limited by memory (e.g., ~2K–10K threads).

-

-

JVM:

-

Each Java thread uses ~1MB stack by default.

-

-

Go:

-

Goroutines scale to millions (they are not OS threads).

-

-

-

-

Execution Limit :

-

Number of threads that can run at the same time on a core.

-

Only a limited number can be executed concurrently per core.

-

Can be 1 or 2 (with SMT/hyper-threading).

-

SMT (Simultaneous Multithreading) :

-

Is a CPU-level technique that allows a single physical core to execute multiple threads simultaneously by sharing its internal execution resources.

-

Hyper-threading :

-

It's a implementation of SMT by Intel.

-

A single core can run two hardware threads, allowing limited parallelism per core.

-

-

-

Example :

-

1 thread, 1 core

-

Thread runs directly on the core.

-

-

N threads, 1 core

-

OS time-slices threads — concurrent, not parallel.

-

-

N threads, M cores

-

Threads are distributed across cores and context-switched as needed.

-

-

N threads, M cores

-

Potential parallel execution, if the OS schedules them simultaneously.

-

-

-

-

Affinity :

-

Threads can be pinned to specific cores to improve cache locality and reduce context switching.

-

-

Load balancing :

-

OS may migrate threads between cores to balance CPU load.

-

Thread-Safety

-

Code is thread-safe if it behaves correctly when accessed concurrently by multiple threads.

-

No race conditions.

-

No data corruption.

-

No undefined behavior.

-

-

Expected output is always produced, regardless of timing.

-

Code is thread-safe if it functions correctly when executed concurrently by multiple threads.

-

Immutability :

-

Immutable objects cannot be changed, inherently thread-safe.

-

-

Thread-Local Storage :

-

Store separate variable copies for each thread.

-

Example :

thread_localin C++,ThreadLocal<T>in Java,threading.local()in Python.

-

-

Lock-Free or Wait-Free Algorithms :

-

Data structures avoiding locks but preventing race conditions.

-

Advanced : Requires atomic operations and memory ordering.

-

-

Avoid Shared State :

-

Design so threads do not share mutable data; use message-passing or immutable queues.

-

Example : Actor model (Erlang, Akka in Scala).

-

Fibers

-

Fiber: lightweight thread , manually scheduled, cooperatively multitasked.

-

Not OS-managed; must explicitly yield control.

-

Create, switch, resume fibers manually.

-

Hard to use correctly; OS doesn't schedule them.

-

-

Optimize task switching within a single thread.

-

Each fiber has its own stack.

-

More like user-space threads, no preemption.

-

Use Case :

-

User-level schedulers

-

High-performance I/O systems

-

Green thread implementations

-

-

Exemples :

-

Found in lower-level systems like Windows fibers, libfiber, or languages like Ruby , C++ , and Rust .

-

-

[cppcon 2017] "Not currently in C++. Available via Boost.Fiber"

Green Thread

-

A thread that is scheduled by a runtime library instead of natively by the underlying OS.

-

Used to emulate multithreading without OS support.

-

[cppcon 2017] "Not currently in C++. Most OSs support native threads".

-

Not widely used outside of:

-

Go.

-

Erland.

-

Sort of.

-

-

Java.

-

In older versions.

-

-

Goroutine

-

Lightweight user-space thread , managed by Go runtime, not OS.

-

Created with

gokeyword:go myFunction -

Multiplexed onto fewer OS threads by Go scheduler.

Comparisons

-

OS Threads

-

Goroutines are cheaper: Go can run thousands of goroutines on a few OS threads.

-

Less control: You don’t pin goroutines to cores or manage priorities.

-

Automatic scheduling: Go’s scheduler handles context switching without OS involvement.

-

-

Fibers/Coroutines

-

Goroutines are preemptively scheduled , unlike pure coroutines which require manual yielding.

-

More natural for writing blocking-style code that looks synchronous.

-

-

Green Threads

-

Goroutines are a modern green-thread model but include runtime preemption and parallelism support on multiple cores.

-

Advantages

-

Simple syntax:

go func() -

Low memory and CPU overhead.

-

Built-in channels provide CSP-style synchronization.

-

Easier to write concurrent code with synchronous semantics.

Disadvantages

-

Less control than OS threads .

-

Go runtime scheduling overhead may become a bottleneck in specific low-latency or real-time workloads.

-

Blocking syscalls (C FFI) can still tie up OS threads unless handled specially.

Strategies

-

See Physics Engines#Theory for strategies.

-

Ex : Spin Lockless > Lockless > Sync Primitives.

-

Dedicated Threads / Static Partitioning / Domain-Specific Threads

-

Assign specific long-running tasks to fixed threads.

-

Characteristics:

-

Specialized threads (e.g., physics thread only does physics).

-

No dynamic task assignment.

-

Threads run continuously.

-

-

Used in:

-

Older game engines, embedded systems, latency-critical apps.

-

Older Unreal Engine versions: separate threads for rendering, physics.

-

-

When to Stick :

-

Game performance acceptable.

-

Stability/debug priority over throughput.

-

Workloads not easily parallelizable.

-

-

Dedicated thread may call job system for subtasks.

Pros

-

Simple to implement/debug.

-

Low latency.

-

Predictable (no unrelated contention).

Cons

-

Poor CPU utilization (idle threads waste cores).

-

Hard to scale.

Implementation

-

No Scheduler: thread manages own work manually.

-

No task queue.

Transition to: Job System

-

Technical Hurdles

-

Task Granularity: Dedicated threads handle coarse work (e.g., "whole physics step"), while jobs need fine-grained tasks (e.g., "collision check between A and B").

-

Synchronization: Dedicated threads often use locks; jobs rely on dependencies/atomics.

-

Latency Sensitivity: Jobs introduce scheduling overhead (bad for real-time threads like rendering).

-

-

Architectural Shifts

-

From "Owned Data" to "Shared Data": Dedicated threads often own their data (e.g., physics thread owns physics state), while jobs assume data is transient/immutable.

-

Debugging Complexity: Race conditions in jobs are harder to trace than linear thread execution.

-

Job System

About

-

Unit of work : task/function executed asynchronously.

-

Scheduled and managed by runtime/thread pool/scheduler.

-

Jobs require execution context and synchronization.

-

Like a thread pool but with:

-

Fine-grained tasks, dependencies, work stealing.

-

Workflow

-

A job (e.g., compute something, handle request) is created.

-

It's added to a job queue .

-

A scheduler picks jobs from the queue.

-

A worker (thread/fiber/goroutine) executes the job.

-

Synchronization primitives are used inside jobs if they access shared state.

Job or Task?

-

"Job is a self contained task with parameters."

-

They are closely related and often used interchangeably, but there are distinctions depending on context, level of abstraction, and language/runtime.

-

A task can be considered a specialized kind of job.

-

In many libraries and frameworks, the terms are synonymous in practice but may imply different underlying models (threaded vs. async).

-

.

.

Job Queue

-

Is a data structure that holds pending jobs (tasks) to be executed by workers (threads, fibers, goroutines, etc.).

-

It is typically implemented as a FIFO queue, but can vary depending on scheduling strategy.

-

A buffer that stores jobs waiting to be run.

-

A job queue is often implemented using an array or linked list, with concurrency controls.

-

Tipos :

-

FIFO Queue

-

First In First Out.

-

Basic job queue, executed in submission order

-

-

Priority Queue

-

Jobs with priority levels, higher priority first

-

-

Ring Buffer

-

Fixed-size circular buffer, often for performance

-

-

Deque

-

Double-ended queue

-

-

Load-balancing / Work-stealing

-

Building a Job System in Rust .

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

Useful to understand its Ring Buffer.

-

-

.

.

-

"Nonetheless, I really want to do what Naughty Dog did with their engine: Jobify the entire thing. EVERYTHING will run on this job system, with a few significant exceptions: Startup, shutdown, logging and IO. Everything that runs on the job system will push local jobs."

-

-

Advantages

-

Fine-Grained Workload Distribution :

-

Jobs are small units of work, allowing better load balancing across threads.

-

Reduces idle time by keeping all threads busy with smaller tasks.

-

-

Scalability :

-

Jobs can be dynamically scheduled across available threads, scaling well with CPU core count.

-

Better suited for heterogeneous workloads than static thread partitioning.

-

-

Reduced Thread Overhead :

-

Avoids frequent thread creation/destruction by reusing a fixed pool of worker threads.

-

More efficient than per-task threading (e.g., spawning a thread for each small task).

-

-

Dependency Management :

-

Jobs can express dependencies (e.g., "Job B runs after Job A"), enabling efficient task graphs.

-

Better than manual synchronization in raw thread-based approaches.

-

-

Cache-Friendly :

-

Jobs can be designed to process localized data, improving cache coherence compared to thread-per-task models.

-

-

Flexibility :

-

Supports both parallel and serial execution patterns.

-

Easier to integrate with other systems (e.g., async I/O, game engines, rendering pipelines).

-

Disadvantages

-

Scheduling Overhead :

-

Managing a job queue and dependencies introduces some runtime overhead.

-

May not be worth it for extremely small tasks (nanosecond-scale work).

-

-

Complex Debugging :

-

Race conditions and deadlocks can be harder to debug than single-threaded or coarse-grained threading.

-

Job dependencies can create non-linear execution flows.

-

-

Potential for Starvation :

-

Poor job partitioning can lead to some threads being underutilized.

-

Long-running jobs may block others if not split properly.

-

-

Dependency Complexity :

-

While dependencies are powerful, managing complex job graphs can become unwieldy.

-

Requires careful design to avoid bottlenecks.

-

-

Latency for Small Workloads :

-

If job submission and scheduling latency is high, it may not be ideal for ultra-low-latency tasks.

-

Explanations

-

Multithreading with Fibers+Jobs in Naughty Dog engine .

-

Fibers were highly praised, it was very appreciated.

-

About libs :

-

"There are so few functions that I wouldn't bother with a library".

-

-

From what I understood of the strategy :

-

Everything is transformed into a job and scheduled to run asynchronously across multiple threads.

-

This is handled automatically by the job system.

-

All new jobs added to the queue are executed completely spread out, out of order, and with some jobs in between.

-

-

Setup :

-

6 worker threads, one for each CPU core.

-

160 fibers.

-

800-1000 jobs per frame in The Last of Us Remastered, at 60Hz.

-

3 global job queues.

-

.

.

-

-

Jobs :

-

"Jobfy the entire engine, everything needs to be a job".

-

EXCEPT I/O Threads:

-

sockets, file I/O, system calls, etc.

-

"There are system threads".

-

"Always waiting (sleeping) and never do expensive processing of the data".

-

-

.

.

-

-

Fibers :

-

"It's just a call stack".

-

Pros :

-

Easy to implement in an existing system.

-

-

Cons :

-

"System synchronization primitives can no longer be used"

-

Mutex, semaphore, condition variables, etc.

-

Locked to a particular thread. Fibers migrate between threads.

-

-

Synchronization has to be done at the hardware level.

-

Atomic spin locks are used almost everywhere.

-

Special job mutex is used for locks held longer.

-

Puts the current job to sleep if needed instead of spin lock.

-

-

-

-

Fibers and their call stacks are viewable in the debugger, just like threads.

-

Can be named/renamed.

-

Indicates the current job.

-

-

Crash handling

-

Fiber call stacks are saved in the core dumps just like threads.

-

-

"Fiber-safe Thread Local Storage (TLS)".

-

Clang had issues with this in 2015.

-

-

Use adaptive mutexes in the job system.

-

Spin and attempt to grab lock before making a system call.

-

Solves priority inversion deadlocks.

-

Can avoid most system calls due to initial spin.

-

-

-

FrameParams :

-

Data for each displayed frame.

-

Contains per-frame state:

-

Frame number.

-

Delta time.

-

Skinning matrices.

-

-

Entry point for each stage to access required data.

-

It's a non-disputed resource.

-

State variables are copied into this structure every frame:

-

Delta time.

-

Camera position.

-

Skinning matrices.

-

List of meshes to render.

-

-

Stores start/end timestamps for each stage: game render, GPU, and flip.

-

HasFrameCompleted(frameNumber) -

We have 16 FrameParams to check, but it's not 16 FrameParams worth of memory, as they are now freed.

-

"The output of one frame is the input of the next".

-

-

-

-

Written in C++.

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

Jobs :

-

"Jobs with ideal duration 500us - 2000us".

-

Priority-based FIFO

-

First In First Out.

-

-

-

"" FIBER ""

-

Set of jobs that always run serially and sequentially with an associated block of memory.

-

"We have 3-4 fibers".

-

They are a convenience, as they are easier to understand than a mess of jobs.

-

"Easier to describe".

-

-

-

Resource .

-

Something that can be accessed.

-

Theoretical.

-

Havok World, player profile, AI data, etc.

-

-

Policies

-

>> Asserts << .

-

This was the biggest tip given.

-

It's an insanely difficult job, and without asserts it would be impossible.

-

-

Describe what you can do with a resource.

-

-

Handles.

-

[ ]

-

-

Resolving overlaps :

-

Add job dependencies.

-

Double buffer or cache data.

-

Queue messages to be acted upon later.

-

Restructure your algorithm.

-

{35:04 -> 38:23}

-

-

"I don't know if there were issues with the client-server architecture".

-

Job System in Unity

-

.

.

Thread Pools

TLDR

-

It's a middle ground between Dedicated Threads and a Job System.

-

I feel it's a "soft" version of a Job System.

-

Job systems are not strictly better than a Thread Pool—they’re more specialized.

-

Thread pools win for simplicity and low-latency tasks.

-

For most games, a hybrid approach is optimal.

-

About

-

A collection of pre-instantiated reusable threads.

-

A pool of generic threads that pull tasks from a shared queue.

-

Reduces overhead from frequent thread creation/destruction.

-

Thread pools are better than Dedicated Threads for:

-

Bursty workloads (e.g., loading screens, asset decompression).

-

Scaling across CPU cores.

-

How It Works

-

Tasks (arbitrary functions/lambdas) are pushed to a global queue.

-

Idle threads pick up tasks first-come-first-served.

-

No task dependencies (unlike job systems).

Comparisons

-

Thread Pool :

-

For simple fire-and-forget tasks (e.g., logging, file I/O).

-

-

Job System :

-

For complex, data-parallel workloads (e.g., physics, particle systems).

-

-

Stick with Dedicated Threads if:

-

Your game runs smoothly (no CPU bottlenecks).

-

You prioritize simplicity over peak performance.

-

-

Switch to Thread Pool if:

-

You have ad-hoc parallel tasks (e.g., asset loading).

-

You want better CPU usage but aren’t ready for jobs.

-

You need quick parallelism without refactoring.

-

Tasks are independent and coarse-grained.

-

You’re doing I/O or async operations.

-

-

Adopt a Job System if:

-

Your game is CPU-bound and needs max core utilization (e.g., open-world, RTS).

-

You need fine-grained parallelism (e.g., 10,000 physics objects).

-

Work has complex dependencies.

-

You’re willing to restructure code.

-

TBB / oneTBB (Threading Building Blocks)

-

It's a C++ Template Library.

-

Wiki .

-

oneTBB .

-

About .

-

Is a multithreading strategy (or more accurately, a parallel programming framework) rather than just an implementation detail of another strategy.

-

Key Points About TBB:

-

High-Level Parallelism Framework

-

TBB provides a task-based parallel programming model, allowing developers to express parallelism without directly managing threads.

-

It abstracts low-level threading details (like thread creation and synchronization) and instead focuses on tasks scheduled across a thread pool.

-

-

Not Just an Implementation Detail

-

While TBB does implement work-stealing schedulers and thread pools (which could be considered "implementation details"), it is primarily a strategy for parallelizing applications.

-

It competes with other parallelism approaches like OpenMP, raw

std::thread, or GPU-based parallelism (CUDA, SYCL).

-

-

Key Features

-

Task-based parallelism (instead of thread-based).

-

Work-stealing scheduler (for dynamic load balancing).

-

High-level parallel algorithms (

parallelfor,parallelreduce,pipeline, etc.). -

Concurrent containers (e.g.,

concurrentqueue,concurrenthashmap). -

Memory allocator optimizations

tbb::allocatorfor scalable memory allocation.

-

-

Data Parallelism

-

Same operation on different data chunks, e.g., OpenMP.

-

Data Parallelism is a strategy, but SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) is an implementation detail (a CPU feature enabling it).

Actor Model

-

Independent actors messaging asynchronously.

Pipeline Parallelism

-

Split work into stages, like CPU instruction pipelines.

Implementation Detail

-

Building blocks of strategies.

Worker

-

"A thread, fiber, or goroutine that executes jobs."

Scheduler and Task Queue

-

"Decides which worker gets which task."

-

Not needed for Dedicated Threads.

Task Queue

-

"Holds pending work (FIFO, priority-based, etc.)."

Work Stealing

-

A scheduler optimization (workers steal tasks from others).

Coroutine

-

A coroutine is a general programming construct that allows a function to suspend execution and resume later, preserving its state.

-

Usually used in single-threaded environments.

-

Cooperative control

-

A coroutine must explicitly yield control back to the caller or scheduler.

-

-

Resumable state

-

Each coroutine has its own execution context and stack.

-

-

Use Case

-

Asynchronous I/O

-

Event loops

-

Cooperative multitasking

-

-

Examples :

-

Python (

async/await, generators), Kotlin, Lua, C++, C#, JavaScript (async/await), etc.

-

Types

-

Stackless coroutines :

-

Use language support and compiler transformations (e.g.,

async/awaitin JavaScript).

-

-

Stackful coroutines :

-

Can suspend from deeper in the call stack (e.g., Lua, Boost.Coroutine in C++).

-

Asynchronous Programming (Async)

Clarification

-

Async Programming is a paradigm (like event-driven code), not strictly an "implementation detail." It can be a strategy (e.g., Node.js’s event loop) or a tool (e.g.,

async/awaitwith threads). It's often implemented via callbacks/futures/coroutines. -

Async is a programming model that allows non-blocking execution of tasks using event loops and callbacks/futures.

-

Can be concurrent, but not inherently parallel .

-

Tasks can pause and resume without blocking threads.

-

Optimized for I/O-bound workloads.

-

Abstracts event-driven state machines.

Examples

-

Sending an HTTP request without blocking the main thread while waiting for the response.

-

One worker that starts a task , and when waiting, does something else instead of blocking.

Synchronization Primitives

-

Synchronization primitives can come from multiple layers of abstraction; some are provided directly by the operating system, while others are part of programming language libraries or runtime environments.

Operating System (OS) Level

-

Most low-level synchronization primitives originate from the OS.

-

Provided through system calls or kernel APIs .

-

Examples:

-

pthread_mutex,pthread_cond(POSIX Threads on Unix/Linux) -

WaitForSingleObject,CreateSemaphore(Windows API) -

futex(Linux-specific syscall)

-

-

Typically used in C/C++, or by language runtimes internally.

-

Responsibilities of the OS :

-

Manage thread scheduling.

-

Handle context switching and resource blocking.

-

Provide kernel support for locks, semaphores, etc.

-

Programming Language Runtime

-

Languages abstract OS primitives or implement their own strategies.

-

May use OS-level primitives under the hood or optimize further in user-space.

User-Space Libraries

-

Some libraries provide synchronization mechanisms independent of the OS.

-

Often optimized for performance (e.g., lock-free, wait-free algorithms).

-

Examples:

-

Intel TBB (Threading Building Blocks)

-

Boost.Thread (C++)

-

Atomic Operations / Lock-free

-

Low-level CPU-supported operations that are completely indivisible.

-

No locking required.

-

-

I think this exemplifies a bit the necessity of using atomic operations.

-

Atomic Operations

-

See Odin#Atomics .

-

I'm assuming the operations stated here are universal.

-

Atomic Memory Order

-

Modern CPU's contain multiple cores and caches specific to those cores. When a core performs a write to memory, the value is written to cache first. The issue is that a core doesn't typically see what's inside the caches of other cores. In order to make operations consistent CPU's implement mechanisms that synchronize memory operations across cores by asking other cores or by pushing data about writes to other cores.

-

Due to how these algorithms are implemented, the stores and loads performed by one core may seem to happen in a different order to another core. It also may happen that a core reorders stores and loads (independent of how compiler put them into the machine code). This can cause issues when trying to synchronize multiple memory locations between two cores. Which is why CPU's allow for stronger memory ordering guarantees if certain instructions or instruction variants are used.

-

Relaxed:-

The memory access (load or store) is unordered with respect to other memory accesses. This can be used to implement an atomic counter. Multiple threads access a single variable, but it doesn't matter when exactly it gets incremented, because it will become eventually consistent.

-

-

Consume:-

No loads or stores dependent on a memory location can be reordered before a load with consume memory order. If other threads released the same memory, it becomes visible.

-

-

Acquire:-

No loads or stores on a memory location can be reordered before a load of that memory location with acquire memory ordering. If other threads release the same memory, it becomes visible.

-

-

Release:-

No loads or stores on a memory location can be reordered after a store of that memory location with release memory ordering. All threads that acquire the same memory location will see all writes done by the current thread.

-

-

Acq_Rel:-

Acquire-release memory ordering: combines acquire and release memory orderings in the same operation.

-

-

Seq_Cst:-

Sequential consistency. The strongest memory ordering. A load will always be an acquire operation, a store will always be a release operation, and in addition to that all threads observe the same order of writes.

-

-

Note(i386, x64) :

-

x86 has a very strong memory model by default. It guarantees that all writes are ordered, stores and loads aren't reordered. In a sense, all operations are at least acquire and release operations. If

lockprefix is used, all operations are sequentially consistent. If you use explicit atomics, make sure you have the correct atomic memory order, because bugs likely will not show up in x86, but may show up on e.g. arm. More on x86 memory ordering can be found here .

-

Barrier

-

Blocks a group of threads until all have reached the same point of execution.

-

Once all threads arrive, they are released simultaneously.

-

Enables multiple threads to synchronize the beginning of some computation.

-

When

barrier_waitprocedure is called by any thread, that thread will block the execution, until all threads associated with the barrier reach the same point of execution and also callbarrier_wait. -

When a barrier is initialized, a

thread_countparameter is passed, signifying the amount of participant threads of the barrier. The barrier also keeps track of an internal atomic counter. When a thread callsbarrier_wait, the internal counter is incremented. When the internal counter reachesthread_count, it is reset and all threads waiting on the barrier are unblocked. -

This type of synchronization primitive can be used to synchronize "staged" workloads, where the workload is split into stages, and until all threads have completed the previous threads, no thread is allowed to start work on the next stage. In this case, after each stage, a

barrier_waitshall be inserted in the thread procedure.

Semaphore

-

A counter-based synchronization primitive.

-

Can allow multiple threads to access a resource (unlike a mutex, which is binary).

-

Types:

-

Counting Semaphore :

-

Allows

nconcurrent accesses.

-

-

Binary Semaphore :

-

Functions like a mutex.

-

-

-

When waited upon, semaphore blocks until the internal count is greater than zero, then decrements the internal counter by one. Posting to the semaphore increases the count by one, or the provided amount.

-

This type of synchronization primitives can be useful for implementing queues. The internal counter of the semaphore can be thought of as the amount of items in the queue. After a data has been pushed to the queue, the thread shall call

sema_post()procedure, increasing the counter. When a thread takes an item from the queue to do the job, it shall callsema_wait(), waiting on the semaphore counter to become non-zero and decreasing it, if necessary.

Benaphore

-

A benaphore is a combination of an atomic variable and a semaphore that can improve locking efficiency in a no-contention system. Acquiring a benaphore lock doesn't call into an internal semaphore, if no other thread is in the middle of a critical section.

-

Once a lock on a benaphore is acquired by a thread, no other thread is allowed into any critical sections, associted with the same benaphore, until the lock is released.

Recursive Benaphore

-

A recursive benaphore is just like a plain benaphore, except it allows reentrancy into the critical section.

-

When a lock is acquired on a benaphore, all other threads attempting to acquire a lock on the same benaphore will be blocked from any critical sections, associated with the same benaphore.

-

When a lock is acquired on a benaphore by a thread, that thread is allowed to acquire another lock on the same benaphore. When a thread has acquired the lock on a benaphore, the benaphore will stay locked until the thread releases the lock as many times as it has been locked by the thread.

Auto Reset Event

-

Represents a thread synchronization primitive that, when signalled, releases one single waiting thread and then resets automatically to a state where it can be signalled again.

-

When a thread calls

auto_reset_event_wait, its execution will be blocked, until the event is signalled by another thread. The call toauto_reset_event_signalwakes up exactly one thread waiting for the event.

Mutex (Mutual exclusion lock)

-

A Mutex is a mutual exclusion lock It can be used to prevent more than one thread from entering the critical section, and thus prevent access to same piece of memory by multiple threads, at the same time.

-

Mutex's zero-initializzed value represents an initial, unlocked state.

-

If another thread tries to acquire the lock, while it's already held (typically by another thread), the thread's execution will be blocked, until the lock is released. Code or memory that is "surrounded" by a mutex lock and unlock operations is said to be "guarded by a mutex".

-

Ensures only one thread accesses a critical section at a time.

-

If another thread tries to lock an already locked mutex, it blocks until the mutex is released.

-

Protect shared variables from concurrent modification.

Problems Prevented by Mutex

-

Race conditions:

-

When multiple threads access and modify a resource simultaneously in an unpredictable way.

-

-

Data inconsistency:

-

Ensures that operations in a critical section are atomic.

-

Challenges of Using Mutex

-

Deadlock:

-

Occurs when two or more threads are stuck waiting for each other to release mutexes.

-

-

Starvation:

-

A thread may wait indefinitely if mutexes are constantly acquired by others.

-

What a Mutex Actually Blocks

-

It blocks other threads from locking the same mutex.

-

If Thread A locks

mutex, Thread B will wait if it tries to lockmutexuntil Thread A unlocks it. -

It does not block threads that don’t try to lock

mutex.

-

-

It does not block the entire function or thread.

-

The rest of your code (outside the mutex) runs normally.

-

Only the critical section (between

lock/unlock) is protected.

-

-

Mutexes Protect Data, Not Functions or Threads.

textures: map[u32]Texture2D textures_mutex: sync.Mutex // Thread A (locks mutex, modifies textures) sync.mutex_lock(&textures_mutex) // 🔒 textures[123] = load_texture("test.png") // Protected sync.mutex_unlock(&textures_mutex) // 🔓 // Thread B (also needs the mutex to touch textures) sync.mutex_lock(&textures_mutex) // ⏳ Waits if Thread A holds the lock unload_texture(textures[123]) sync.mutex_unlock(&textures_mutex)-

The mutex only blocks Thread B if it tries to lock

textures_mutexwhile Thread A holds it. -

If Thread B runs code that doesn’t lock

textures_mutex, it runs freely.

-

-

Mutexes Are Not "Global Barriers". If two threads use different mutexes, they don’t block each other:

// Thread A (uses mutex_x) sync.mutex_lock(&mutex_x) // 🔒 // ... do work ... sync.mutex_unlock(&mutex_x) // 🔓 // Thread B (uses mutex_y) sync.mutex_lock(&mutex_y) // ✅ Runs in parallel (no conflict) // ... do work ... sync.mutex_unlock(&mutex_y)

Example: Task Queue

// --- Shared Task System (Thread-safe) ---

Task_Type :: enum {

UNLOAD_TEXTURE,

LOAD_TEXTURE,

SWAP_SCENE_TEXTURES,

// Add more as needed...

}

Task :: struct {

type: Task_Type,

// Add payload if needed (e.g., texture IDs)

}

task_queue: [dynamic]Task

task_mutex: sync.Mutex

// Thread A (Game Thread): Processes tasks

process_tasks :: proc() {

// 🔒 LOCK the mutex to safely read the queue

sync.mutex_lock(&task_mutex)

defer sync.mutex_unlock(&task_mutex) // 🔓 Unlock when done

// Make a local copy of tasks (optional but cleaner)

tasks_to_process := task_queue[:]

clear(&task_queue) // Empty the shared queue

// 🔓 Mutex unlocked here (defer runs)

// Process tasks WITHOUT holding the mutex

for task in tasks_to_process {

handle_task(task) // e.g., UnloadTexture(...)

}

}

// Thread B (Network Thread): Adds a task

add_task :: proc(new_task: Task) {

// 🔒 LOCK the mutex to safely append

sync.mutex_lock(&task_mutex)

defer sync.mutex_unlock(&task_mutex) // 🔓 Unlock when done

append(&task_queue, new_task)

}

Example: Read and Write

-

READ: MAKES A COPY (wrapped in a mutex), WRITE: MUTEX GUARD

-

For read operations, make a copy of the data to read; for write operations, use a mutex.

-

// Shared data with mutex and atomic pointer for efficient reads

std::mutex data_mutex;

Data* atomic_data_ptr; // Atomic pointer for thread-safe access

// Read Job

void ReadJob() {

Data local_copy;

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(data_mutex); // Optional: Only if data isn't atomically swappable

local_copy = *atomic_data_ptr; // Copy under mutex (or use atomic load)

}

// Use local_copy safely...

}

// Write Job

void WriteJob() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(data_mutex);

// Modify data...

}

Futex (Fast Userspace Mutex)

-

Allows most lock/unlock operations to be done in userspace.

-

System call is only used for contention resolution.

-

Use case : Efficient locking on Linux systems.

User-space atomic spin (with

cpu_relax

) vs Futex

-

For very short waits (tens–thousands of CPU cycles) a user-space atomic spin (with

cpurelax) is lower latency than a futex because it avoids syscalls and context switches. -

For longer waits (microseconds and above, or whenever contention is non-trivial) a futex is far better overall because it blocks the thread in the kernel and does not burn CPU.

One Shot Event

-

One-shot event.

-

A one-shot event is an associated token which is initially not present:

-

The

one_shot_event_waitblocks the current thread until the event is made available Theone_shot_event_signalprocedure automatically makes the token available if its was not already.

Parker

- A Parker is an associated token which is initially not present:

-

The

parkprocedure blocks the current thread unless or until the token is available, at which point the token is consumed. Thepark_with_timeoutprocedures works the same asparkbut only blocks for the specified duration. Theunparkprocedure automatically makes the token available if it was not already.

Spinlock (Spin until Mutex is unlocked)

-

Like a mutex, but instead of blocking, it repeatedly checks (spins) until the lock becomes available.

-

Low overhead but inefficient if held for long.

-

Use case : Short critical sections on multiprocessor systems.

Read-Write Mutex / Read-Write Lock

Naming

-

A read–write lock (RW lock) lets many readers hold the lock concurrently but only one writer at a time. Calling it a read–write mutex is common and acceptable; it’s a mutual-exclusion primitive with two modes (shared/read and exclusive/write).

Read-Write Mutex

-

Allows multiple readers or one writer , but not both.

- Read-write mutual exclusion lock. -

An

RW_Mutexis a reader/writer mutual exclusion lock. The lock can be held by any number of readers or a single writer. -

This type of synchronization primitive supports two kinds of lock operations:

-

Exclusive lock (write lock)

-

Shared lock (read lock)

-

-

When an exclusive lock is acquired by any thread, all other threads, attempting to acquire either an exclusive or shared lock, will be blocked from entering the critical sections associated with the read-write mutex, until the exclusive owner of the lock releases the lock.

-

When a shared lock is acquired by any thread, any other thread attempting to acquire a shared lock will also be able to enter all the critical sections associated with the read-write mutex. However threads attempting to acquire an exclusive lock will be blocked from entering those critical sections, until all shared locks are released.

How it works internally

-

Most efficient implementations are user-space fast paths plus a kernel-assisted wait path.

-

State word (atomic integer).

-

Encodes reader count and writer flag (and sometimes waiter counts or ticket/sequence numbers).

-

Example encoding:

-

low bits or a counter = number of active readers

-

one bit = writer-active flag

-

optional fields = number of waiters or ticket counters

-

-

-

Fast path (uncontended):

-

AcquireRead: atomically increment reader count if writer bit is 0. -

AcquireWrite: atomically set writer bit (CAS) if reader count is 0 and writer bit was 0; if successful, you’re owner.

-

-

Slow path (contended):

-

If fast path fails (writer present or racing), the thread either spins briefly or goes to sleep on a wait queue associated with the lock (on Linux typically via

futex, on Windows via wait-on-address / kernel wait objects). -

Waiting threads sleep until a waking operation (writer release or explicit wake) changes the state and wakes them.

-

-

Release:

-

ReleaseRead: atomically decrement reader count. If reader count becomes 0 and a writer is waiting, wake one writer. -

ReleaseWrite: clear writer bit and wake either waiting writers (writer-preferring) or all readers (reader-preferring / fair), depending on policy.

-

Comparison

RW_Mutex

vs Double-Buffering

-

.

.

SRW Lock (Slim Reader/Writer lock) (Windows only)

-

It's a lightweight synchronization primitive in Windows that allows multiple concurrent readers or a single writer.

-

Supports shared mode (multiple readers) and exclusive mode (one writer).

-

Unfair by design; a writer may bypass waiting readers.

-

Very small footprint (pointer-sized structure).

-

Non-reentrant: a thread must not acquire the same SRW lock twice in the same mode.

Once

-

Once action.

-

Oncea synchronization primitive, that only allows a single entry into a critical section from a single thread.

Ticket Mutex

-

Ticket lock.

-

A ticket lock is a mutual exclusion lock that uses "tickets" to control which thread is allowed into a critical section.

-

This synchronization primitive works just like spinlock, except that it implements a "fairness" guarantee, making sure that each thread gets a roughly equal amount of entries into the critical section.

-

This type of synchronization primitive is applicable for short critical sections in low-contention systems, as it uses a spinlock under the hood.

Condition Variable

-

Allows threads to sleep and be awakened when a specific condition is true.

-

It's a rendezvous point for threads waiting for signalling the occurence of an event. Condition variables are used in conjuction with mutexes to provide a shared access to one or more shared variable.

-

A typical usage of condition variable is as follows:

-

A thread that intends to modify a shared variable shall:

-

Acquire a lock on a mutex.

-

Modify the shared memory.

-

Release the lock.

-

Call

cond_signalorcond_broadcast.

-

-

A thread that intends to wait on a shared variable shall:

-

Acquire a lock on a mutex.

-

Call

cond_waitorcond_wait_with_timeout(will release the mutex). -

Check the condition and keep waiting in a loop if not satisfied with result.

-

-

Wait Group

-

Wait group is a synchronization primitive used by the waiting thread to wait, until all working threads finish work.

-

The waiting thread first sets the number of working threads it will expect to wait for using

wait_group_addcall, and start waiting usingwait_group_waitcall. When worker threads complete their work, each of them will callwait_group_done, and after all working threads have called this procedure, the waiting thread will resume execution. -

For the purpose of keeping track whether all working threads have finished their work, the wait group keeps an internal atomic counter. Initially, the waiting thread might set it to a certain non-zero amount. When each working thread completes the work, the internal counter is atomically decremented until it reaches zero. When it reaches zero, the waiting thread is unblocked. The counter is not allowed to become negative.

Double-Buffering

-

It's a technique, not a synchronization primitive.

-

Interesting when you have frequent reads and infrequent writes (e.g., rendering data, physics state).

-

How It Works :

-

Maintain two buffers: a front buffer (for readers) and a back buffer (for writers).

-

Readers always access the front buffer (no locks needed).

-

Writers modify the back buffer, then atomically swap the buffers when done.

-

#include <atomic>

#include <mutex>

struct GameState {

int player_health;

float enemy_positions[1000];

// ... other game data

};

// Double-buffered data

std::atomic<GameState*> front_buffer; // Readers access this (lock-free)

GameState back_buffer; // Writers modify this

std::mutex write_mutex; // Protects back_buffer modifications

// Initialize

void Init() {

front_buffer.store(new GameState(), std::memory_order_relaxed);

}

// Read Job (Lock-Free)

void ReadJob() {

GameState* current = front_buffer.load(std::memory_order_acquire);

// Safely read from 'current' (no locks needed!)

int health = current->player_health;

// ...

}

// Write Job (Synchronized)

void WriteJob() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(write_mutex);

// Modify the back buffer

back_buffer.player_health = 100;

// Swap buffers (atomic, readers see the new state immediately)

GameState* old = front_buffer.exchange(&back_buffer, std::memory_order_release);

// Optional: Reuse 'old' for next write to avoid allocations

std::swap(back_buffer, *old);

}

// Cleanup

void Shutdown() {

delete front_buffer.load();

}

-

Scenario: Writer Removes an Element in Double Buffering

-

Initial State:

-

front_buffer→[A, B, C, D](readers see this) -

back_buffer→[A, B, C, D](writer modifies this)

-

-

Writer Removes

C:-

Writer modifies

back_buffer→[A, B, D] -

Writer swaps

frontbufferandbackbuffer(nowfrontbufferpoints toA, B, D).

-

-

Reader Access:

-

Before Swap: A reader sees

A, B, C, D(oldfrontbuffer). -

After Swap: New readers see

A, B, D(updatedfrontbuffer).

-

-

What If a Reader Was Accessing

CWhen It Was Removed?-

If a reader was iterating over

frontbuffer(old buffer:A, B, C, D) while the swap happened, it still seesCbecause:-

The reader holds a pointer/reference to the old

frontbuffer(not affected by the swap). -

The writer’s changes only affect new readers (those accessing

frontbufferafter the swap).

-

-

-

-

Is This Safe?

-

Yes:

-

Readers see a consistent snapshot (old buffer remains valid until they finish).

-

No data races (the swap is atomic, and old buffers aren’t modified).

-

-

BUT there are Memory Leak Risks :

-

If the old

front_bufferis discarded, readers holding references to it may access freed memory. -

Strategy :

-

Manage lifetimes collectively.

-

Only "mark something as dead" without freeing it.

-

The free is done when no one is trying to read.

-

-

-

-

Networking Strategies

-

"Is it better to create a thread for every new connection to the server, considering the connection will block thread execution? Or should I unblock the connection and let every pooling occur within the same thread? How often are both strategies used?"

-

Both strategies are common and have trade-offs. The best choice depends on scale, latency requirements, OS constraints, and language/runtime capabilities.

Thread per Connection

-

Each incoming client connection is handled by a dedicated OS thread.

-

Blocking I/O operations are allowed (e.g.,

recv(),send()).-

Thread sleeps when waiting for I/O and resumes when data is available.

-

-

Advantages :

-

Straightforward to implement and debug.

-

Each connection is isolated.

-

Uses OS APIs, so no need for complex event loops.

-

-

Disadvantages :

-

Scalability

-

High memory usage

-

-

Performance

-

High context-switch overhead

-

-

OS limits

-

OS-imposed thread limits

-

-

-

Use cases :

-

Small-scale servers

-

Systems with <1000 concurrent connections

-

Languages like Java or C++ where thread costs are acceptable

-

Single Thread + Non-Blocking I/O (with Multiplexing)

-

All connections are handled on one or few threads.

-

Use non-blocking sockets and a multiplexer (

epoll,kqueue,select). -

Manual polling or event-driven callback system processes I/O.

-

Advantages :

-

Scalability

-

Supports tens of thousands of connections

-

-

Efficiency

-

Minimal context-switching

-

-

Memory

-

Lower per-connection memory overhead

-

-

-

Disadvantages :

-

Complexity

-

Manual state machines or async programming

-

-

Error-prone

-

Harder to debug, manage timeouts, etc.

-

-

Latency

-

Single-threaded bottlenecks under high load

-

-

-

Use cases :

-

High-concurrency servers (e.g., web servers, proxies)

-

Event-driven platforms (e.g., Node.js, Nginx)

-

Languages with async runtimes (Rust/Tokio, Python/asyncio, Java NIO, etc.)

-

Hybrid Models (Thread Pools + Non-blocking I/O)

-

Use a small thread pool (e.g., per-core or per-socket).

-

Each thread runs an event loop handling multiple connections.

-

Scales well and reduces the risk of single-thread saturation.

-

Common in Go, Netty (Java), libuv (Node.js).